Monday, 30 September 1940: Daylight Defeat

By mid-September 1940, losses to the German bomber force were becoming critical. Moreover, these twin-engine machines were intended to provide close support to the advancing army, so lacked the range or bombloads to wage a strategic bombing campaign. Furthermore, despite its other attributes, the twin-engine Me 110 had ultimately proved disappointing as an escort fighter, and the single-engine Me 109, with sufficient fuel for only twenty minutes flying time over London, lacked the range to be an offensive fighter.

After the turning point on 15 September 1940, when it was clear that the RAF remained undefeated, Hitler postponed his proposed seaborne invasion two days later. Reichsmarschall Göring, however, still believed, quite wrongly, that his Luftwaffe alone could defeat the RAF, and so for the last two weeks of September 1940, the daylight raids on Britain continued.

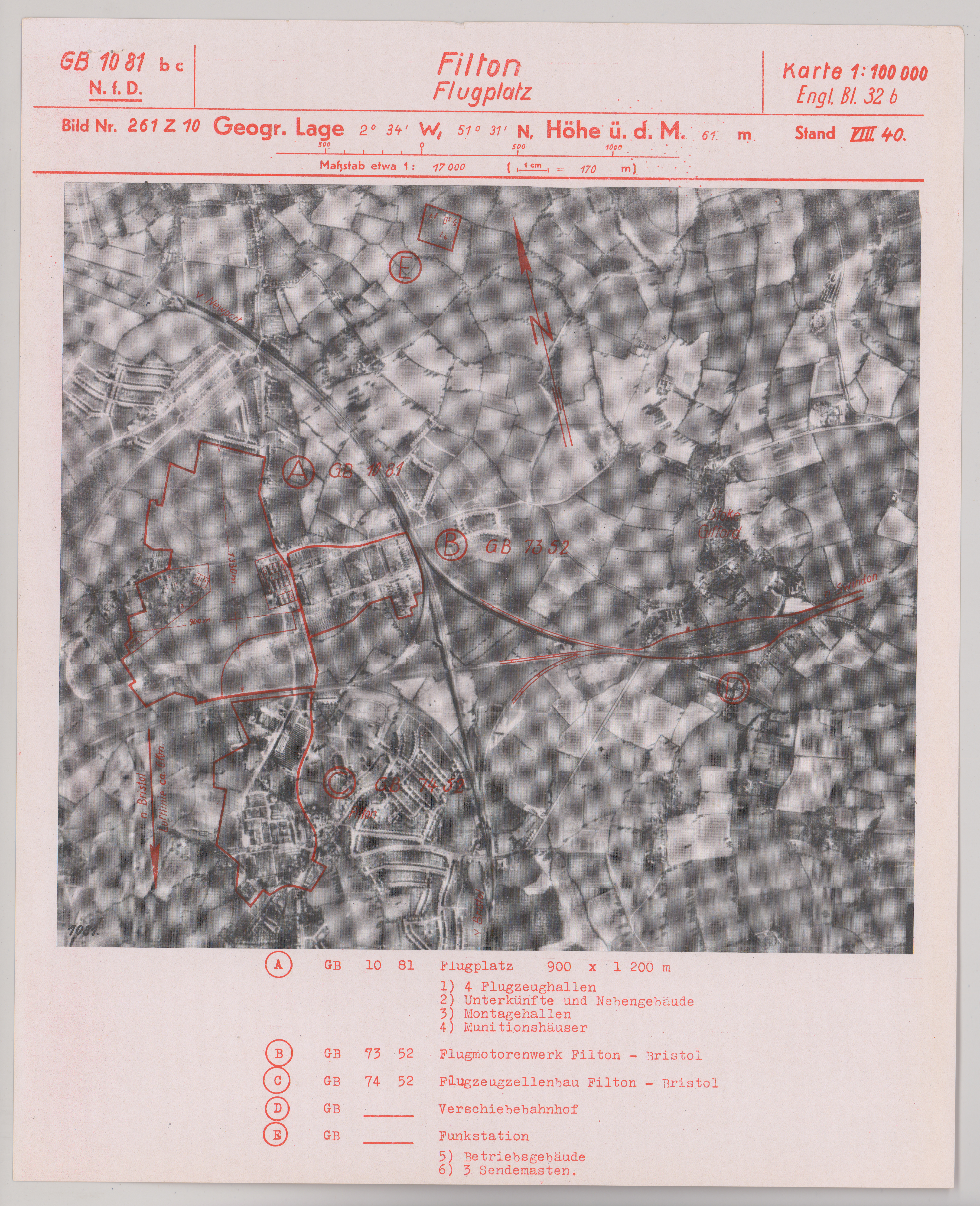

Instead of continuing to focus on London, however, after Hitler’s postponement of Operation Seelöwe a new phase of battle began, primarily targeting British aircraft factories. Some of these raids would be particularly successful, notably KG55’s devastating raids on the Bristol Aeroplane Company at Filton on 25 September 1940, and the virtual destruction of the Supermarine factory at Woolston the following day.

On 27 September 1940, the Germans returned to the West Country, bound for Parnall Aircraft at Yate, intending to duplicate their recent Filton success, but their way was barred by RAF fighters, the raid turned about and heavy losses inflicted on the Me 110s involved. Nonetheless, on 30 September 1940, KG55 returned to the West Country: target Westland Aircraft at Yeovil. Cloud, however, obscured the target, leading to the Heinkels bombing and devastating picturesque Sherborne, in Dorset, which was of no military significance.

All of these raids are deconstructed in detail, the resulting narrative providing a minute-by-minute, blow-by-blow, 360 account, proliferated with first-hand accounts, in my Daylight Defeat: 18 September 1940 – 30 September 1940, this being the sixth of the eight-volume official history I have recently completed for The Battle of Britain Memorial Trust, published by Pen & Sword.

Although KG55 had achieved success at Filton and Woolston, losses were heavy, as the unit’s history relates: ‘September 1940 was the hardest month of action for everyone involved in the Battle of Britain, friend and foe alike. KG55 alone lost twenty aircraft and fifteen crews, not to mention those wounded. Time and time again Geschwader personnel from various roles had to – and wanted to – step in as gunners … Oberleutnant Miller often flew along, bypassing a preventative order by choosing a military rank – he was the III Gruppe’s senior physician. So too did the Geschwader Meteorological Officer, Friedrich Wobst, all these comrades helping relieve the burden on the aircrews, who are exhausted. In the thirty days of September 1940, the Luftwaffe lost irreplaceable experience: four Geschwader Kommodore, thirteen Gruppenkommandeur, and twenty-eight Staffelkapitän’.

These were serious losses – which were unsustainable in terms of aircrew or aircraft. By 30 September 1940, the Kampfgeschwadern had been reduced to 52% in aircraft strength and aircrew numbers were only 68%.

On 27 September 1940, on the ill-fated Yate raid, Erprobungsgruppe 210 lost 40% of its strength and its third Gruppenkommandeur of the Battle of Britain, Hauptmann Martin Lutz, who had just received the Ritterkreuz for his part in the destruction of Supermarine; this previously dangerous fighter-bomber unit would not participate in any further significant activity of England. Indeed, the same day also saw exceptionally heavy losses to Luftflotte 2’s Zerstörer force, effectively neutralizing the Me 110 as a day-fighter – a bitter pill for Reichsmarschall Göring, having placed so much faith in the twin-engine heavy fighter. This was especially galling for the Luftwaffe chief considering how well the earlier phases of the Battle of Britain, fought over shipping and coastal targets, had begun for his 110s.

The Me 109 force was at a disadvantage owing to the single-engine fighter’s limited range and restricted freedom of action given the need to escort slower and more vulnerable bombers. The 109 force was also significantly weakened. By 28 September 1940, for example, JG53 only had ninety-three aircraft, only seventy-two of which were serviceable – just 60% of the Geschwader’s authorized strength of 124 Me 109s.

This shortage of operational Me 109s was compounded by Göring’s insistence that one Staffel in every Gruppe would become fighter-bombers. The German aircraft factories were simply unable to keep pace with the demand for replacement machines – in September 1940, for example, Germany produced 218 single-engine fighters. Britain, on the other hand, whose aircraft industry was under attack and had suffered the virtual destruction of Supermarine on 26 September 1940, manufacturer 467 – only twenty-nine less Spitfires and Hurricanes were manufactured than in July 1940.

Inadequate provision for the supply of replacement aircraft meant, in simple terms, the level of superiority required to defeat such an opponent as Fighter Command was impossible to achieve. This was partly because such an intense and drawn-out aerial campaign was unprecedented and therefore the number of replacement machines now required, and the production facilities required, had not previously been considered. Quite simply, the Luftwaffe lacked the means, in every respect, to destroy the British aircraft industry – in fact, British production figures confirm that the greater the attacks and danger of invasion, the workers’ output actually increased. Suffice it to say that on 1 October 1940, the Germans had 275 operational Me 109s – compared to the RAF’s 732 serviceable single-engine fighters recorded on 28 September 1940.

In terms of pilots, by 30 September 1940, taking JG53 as an example, the Geschwader had suffered twenty-four killed or missing, eighteen more were POWs and six had been wounded. In sum, at the start of the battle, in July 1940, JG53’s establishment was 113 pilots, of which forty-eight, 40%, were now out of action. The Jagdwaffe had now reached the point whereby it was unable to replace casualties with experienced pilots, these places being filled by increasingly young and inexperienced officer candidates and junior NCOs fresh from flying training schools. Indeed, 30 September 1940 was one of the worst-ever days for the highly successful JG26: four pilots lost offset against only seven combat claims (and those were inflated as only two can be confirmed).

German flying training programmes lacked urgency, and the majority of pilots trained and available were bomber pilots who could not be swiftly re-trained as fighter pilots. Conversely, RAF Training Command was now working at full stretch, prioritizing producing fighter pilots, given the current need. Replacement pilots, although lacking in combat experience, were made available – not least through the influx of free Poles and Czechs, whose English had sufficiently improved for there to be two Polish and one Czech squadron operational, in addition to pilots from those and free men of other occupied nations to be embedded throughout Fighter Command’s squadrons. Of course, RAF pilots enjoyed one advantage over the Luftwaffe, in that if they survived being shot down over Britain, they would soon fight again – whereas Luftwaffe airmen brought down over England faced long years in a prison camp.

Despite deficiencies in manpower and aircraft, there were occasions between 18 September 1940 and 30 September 1940 that the Me 109 pilots demonstrated how lethal they could still be when left free to roam, with the immeasurable advantages of height, sun and surprise. A primary case in point is 27 September 1940, when in the battles over southern England, twenty-six RAF fighters were destroyed, with nineteen pilots killed – a day considered by Churchill to be the Battle of Britain’s third greatest day.

During this phase, the Germans continued attacking on a broad front, often from Rochester to Portland, and launching simultaneous attacks on the 10 and 11 Group areas in an attempt to overwhelm the defences. In sum, Luftwaffe resources were too thinly spread and target selection was inconsistent and confused. Moreover, the dwindling bomber force was attacking both night and day – and the night bomber force was already substantial, in itself weakening the daytime effort, with anything between 150 – 300 bombers operating over Britain at night, mainly attacking London and Liverpool.

With diminishing resources and unsustainable losses, the German bombers, excepting the fast and heavily armed Ju 88, were now pulled out of the day battle to attack Britain under the much safer cloak of darkness. Arguably, then, the Germans had lost the daylight battle by 30 September 1940. Going forward, the last month of day-fighting, October 1940, would feature high-flying fighter sweeps, fighter-bomber attacks, and small numbers of heavily escorted Ju 88s occasionally sallying forth along with lone Ju 88s flying nuisance attacks when weather permitted. Again, such plan as there was by day continued targeting the British aircraft industry – but whatever lay ahead, with winter fast approaching and with it the air fighting season’s conclusion, the effect was unlikely to impede British aircraft production.

That being so, and considering the postponement of Operation Seelöw, the crisis had passed.

Dilip Sarkar MBE FRHistS FRAeS

Dilip Sarkar’s YouTube Channel.

Dilip Sarkar’s Website.

Find Dilip Sarkar on Facebook.

The Battle of Britain Memorial Trust CIO.

Order your copy here.

By Author Dilip Sarkar MBE

Posted September 30th 2024